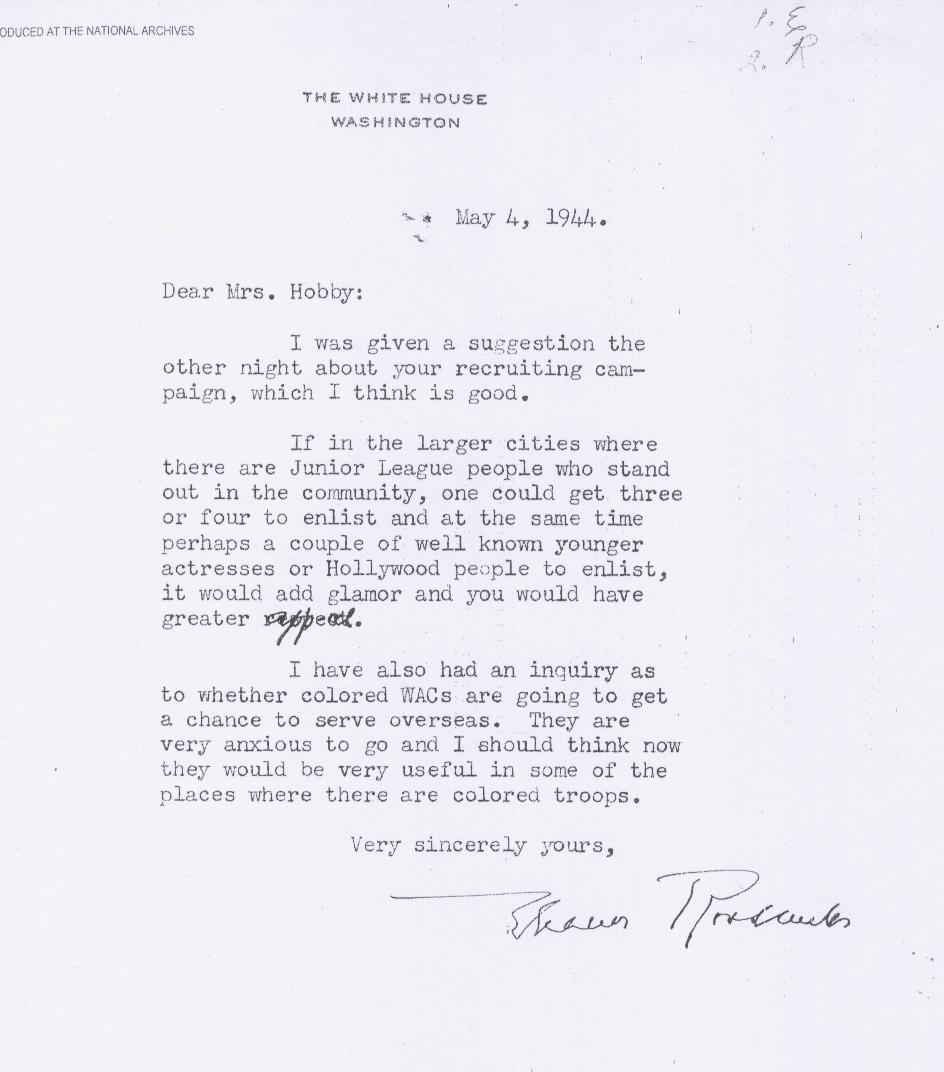

Copy of Roosevelt's letter supporting African-American members of the Women's Army Corps.

Source: National Archives and Records Administration

For More Information on Eleanor Roosevelt, the Women's Army Corp, and How You Can Obtain and Use Historic Documents:

History Comes Alive as Words and Images Come to the Web

"A Good Lady's" Words Teach Another Generation

by Jean Gossman

Seventh-grader Claire Eleanor Boston struck gold researching a women’s history paper when she got some help of a sort from the historic women themselves. One was even her middle-namesake.

The paper’s topic, World War II-era discrimination against African-Americans in the Women’s Army Corps, came alive after Boston went to the National Archives in October 2006 and dove into a collection of original documents about improving conditions for the servicewomen.

Amid a file of plastic-bagged reports and other documents on the issue was a May 4, 1944, letter to Corps commander Col. Olveta Culp Hobby on slightly yellowed White House stationery from first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Boston’s parents chose their daughter’s middle name to offer her Eleanor Roosevelt as a role model. Before Boston’s research, “I knew who she was and basically what she did. I knew she was a good lady, that she did things to help people,” she said.

But working with primary-source documents refined and deepened Boston’s appreciation of Roosevelt’s influence. “Now you could understand what she was thinking. You got a tiny view into her mind.”

You also get a view into the cultural and social values and vernacular of the day.

Roosevelt’s letter offered Col. Hobby some Corps recruitment suggestions. One, getting a few “younger actresses or Hollywood people” to enlist in the Corps, “would add glamour and you would have greater appeal,” she wrote.

Closing her letter, Roosevelt added that she’d “had an inquiry as to whether colored WACs are going to get a chance to serve overseas. They are very anxious to go, and I should think now they would be very useful in some of the places where there are colored troops.”

Roosevelt’s original signature was a bit light, perhaps faded, according to Boston. The letter was in a protective archival plastic bag. But twelve-year-old Claire Eleanor Boston was thrilled to be working with something that the president’s wife, whose name she bears, had handled and signed herself.

Boston lives in suburban Washington and can readily visit the Archives. But as the Internet matures, citizens unable to go can often find such documents as well. They are finding their treasure online, either as scanned originals, or transcribed and hyperlinked text, often both.

Increasingly, Internet users expect full-text materials to be available online, especially digital natives like Boston who, unlike previous generations, have grown up with the medium since infancy. Roosevelt’s letter is not online yet.

Technicians, editors, historians, and archivists are scrambling to meet the digitization demand from both experienced and novice researchers worldwide. The Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library digitizes materials using guidelines established by the National Archives.

The 82-page guidelines cover complexities that most armchair researchers would never think of in their own quest for historic gold. There are critical issues like color and tonal correction, resolution, and even the color of the paint on the walls in the scanning room. How do you scan embossed seals or three-dimensional artifacts, fragile or not? Plus file-naming conventions, file formats, link stability – the list of technical and administrative challenges is formidable.

In Hyde Park, N.Y., the Roosevelt Library brings in interns from nearby Marist College to do the work in their “clean research room,” Supervisory Archivist Bob Clark said. No papers, notebooks, or personal belongings can be brought in the room. Only a scanner and a laptop are there. Any paper copies printed after scanning are on yellow paper to detect potential theft. All staff and interns must undergo inspection of whatever leaves the room along with them when they complete their work.

In partnership with the FDR Library and other groups, The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project at George Washington University is bringing Roosevelt’s life and work to a huge audience through the Web.

According to the Project’s Web site, by January 2003, they had collected more than 65,000 documents. A third of these have been indexed, creating a database offering researchers more than 15,000 names, 2,200 places, and 2,200 subjects.

Materials to help students and educators learn and teach about Eleanor Roosevelt and her milieu are featured. Their Web site enabled Boston to use an online PDF file of a wartime pamphlet in her research.

The Project collections focus on Roosevelt’s passion for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and democratic ideals — like her support for sending African-American servicewomen to Europe along with their white Corps counterparts.

Project staff are also building an online edition of Roosevelt’s 8,000 syndicated “My Day” newspaper columns written between 1935 and 1962; and a “Mini-Edition Project” documenting the delicate interplay between the venerable Roosevelt and young Senator John F. Kennedy throughout the 1960 presidential campaign and after.

But long before the Internet disseminated her words, image, and voice into homes and classrooms, Eleanor Roosevelt, who taught at a girls’ school, embraced hands-on citizenship education.

Writing for Pictorial View in 1930, Roosevelt said, “I would have our children visit national shrines, know why we love and respect certain men of the past. I would have them see how government departments are run and what are their duties.” She believed children should observe legislative and judicial bodies at work, plus learn about other countries and their interaction. Roosevelt said such a child could then begin to see “how his own life and environment fit into the pattern and where his own usefulness may lie.”

Did the Roosevelt letter or the digitized pamphlet change 12-year-old Claire Boston’s perception of the seemingly ancient World War II years? They’re “more real in a way.” Then, on a less reflective, perhaps more typically pre-teen note, she said that, of all of her project’s resources, the letter “was definitely the coolest thing.”